Introduction

I spent almost my entire life in the Netherlands doing very Dutch things: riding bicycles, complaining about the weather, but after a while I didn’t recognize The Netherlands as the country from my youth.

The Netherlands has always been a small country, but it hasn’t always felt crowded. For a long time, space was managed rather than competed for. Cities were dense but predictable, routines familiar, and social norms quietly enforced by consensus rather than rules.

Over the past decades, that balance has changed. Population growth, driven largely by immigration and urban concentration, has intensified the pressure on a country that was already carefully optimized. Housing is scarcer, infrastructure is stretched, and public spaces feel more transactional than communal. What used to feel compact now feels compressed.

This shift is not only physical but cultural. The shared assumptions that once made daily life frictionless—about language, behavior, pace, and expectations—are less universal. That does not mean worse, but it does mean different. The informal cohesion that relied on similarity and scale is harder to maintain when everything is fuller, faster, and more heterogeneous.

In a country where planning has always been precise, even small increases have large effects. When space is limited, every additional demand becomes visible. Trains feel fuller, neighborhoods noisier, systems less forgiving. The margin for inefficiency—social or logistical—shrinks.

The result is a subtle change in atmosphere. Not dramatic, not catastrophic, but noticeable. The Netherlands still functions exceptionally well, but it no longer feels spacious in any sense of the word. It feels busy, negotiated, and increasingly aware of its own limits.

As those shifts became more noticeable, our relationship with the Netherlands began to change as well. Daily life still worked, but it felt tighter—less forgiving, more crowded, and increasingly defined by competition for space, housing, and attention. What once felt efficient now felt constrained.

For our family, this wasn’t a sudden break but a gradual realization. We weren’t looking for something better in an abstract sense; we were looking for something larger—physically, mentally, and emotionally. More room to move, fewer trade-offs, and a sense that growth didn’t automatically mean friction.

That realization led to a decisive step. We sold almost everything we owned. The house, the cars, and the accumulation of objects that quietly anchor you to a place all went. What remained was the part that mattered.

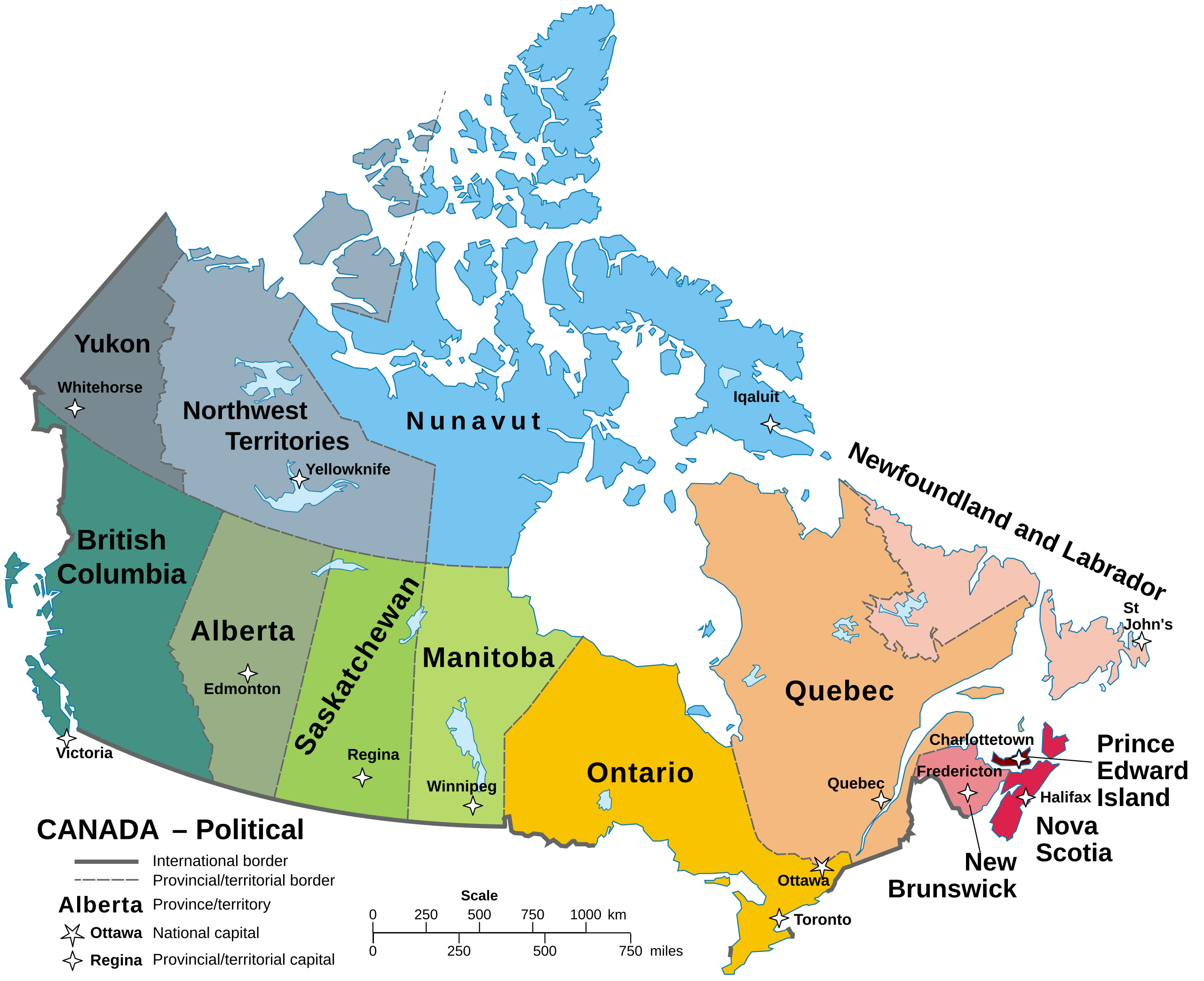

We packed up our lives and moved to Canada, bringing our dog and two cats with us. They had no say in the matter, but they adapted quickly. In many ways, they set the tone: curious, resilient, and entirely unconcerned with borders as long as daily routines continued.

The move wasn’t an escape so much as a recalibration. A choice to trade density for distance, compression for scale, and familiarity for possibility. It marked the end of one chapter, and the deliberate beginning of another.

Now based in Canada, I am learning new skills, such as understanding distances measured in hours instead of kilometers, accepting that Canada is officially metric, but in reality not and explaining to people that no, I am not from Germany, and yes, the Netherlands is a real country.

This website exists somewhere between those two worlds: Dutch practicality and Canadian scale. It is built by someone who believes that life should occasionally involve big decisions, small disasters, and at least one loyal dog who thinks every new country is excellent as long as there is food.